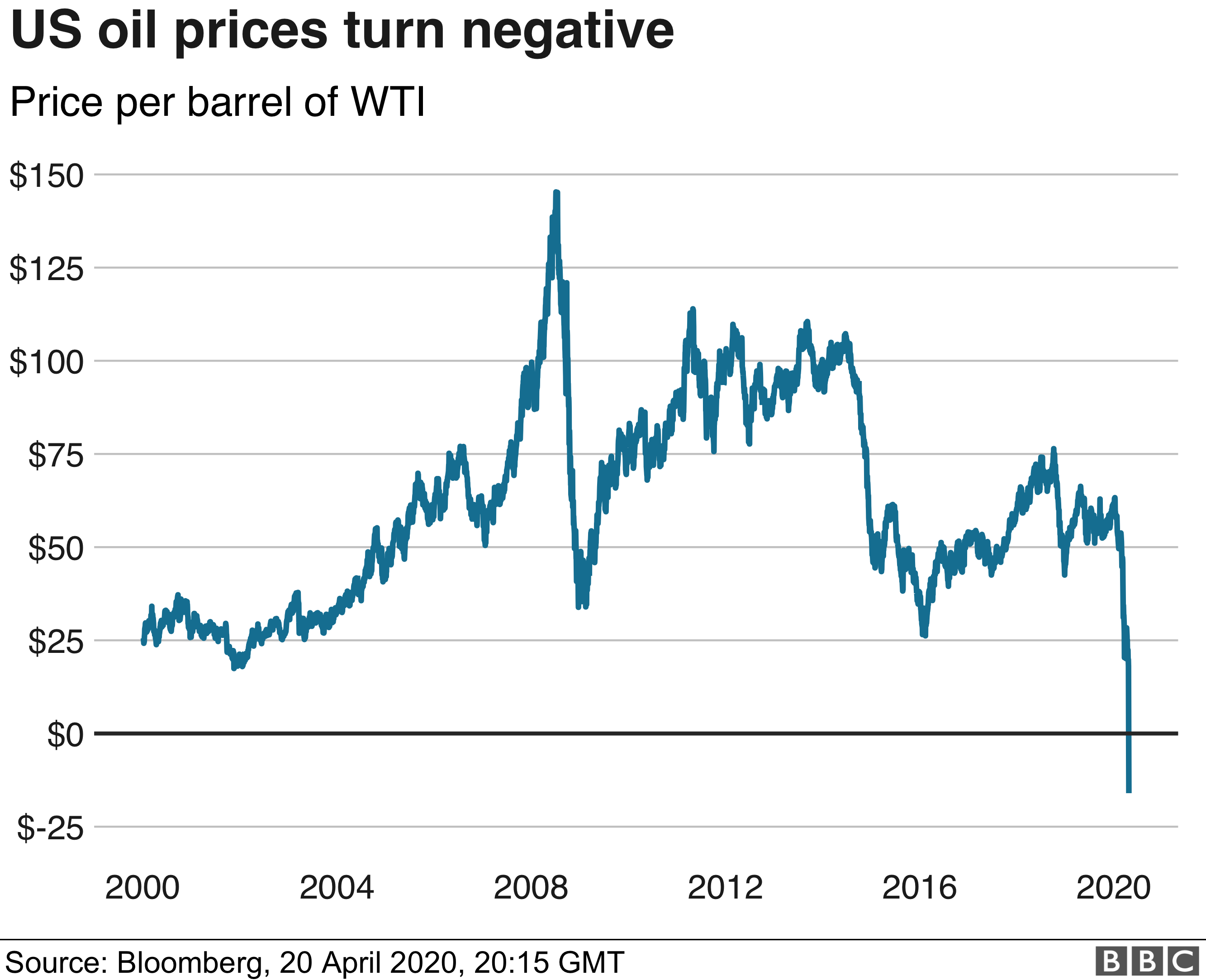

The price of US oil has turned negative for the first time in history.

That means oil producers are paying buyers to take the commodity off their hands over fears that storage capacity could run out in May.

Demand for oil has all but dried up as lockdowns across the world have kept people inside.

As a result, oil firms have resorted to renting tankers to store the surplus supply and that has forced the price of US oil into negative territory.

The price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the benchmark for US oil, fell as low as minus $37.63 a barrel.

“This is off-the-charts wacky,” said Stewart Glickman, an energy equity analyst at CFRA Research. “The demand shock was so massive that it’s overwhelmed anything that people could have expected.”

The severe drop on Monday was driven in part by a technicality of the global oil market. Oil is traded on its future price and May futures contracts are due to expire on Tuesday. Traders were keen to offload those holdings to avoid having to take delivery of the oil and incur storage costs.

June prices for WTI were also down, but trading at above $20 per barrel. Meanwhile, Brent Crude – the benchmark used by Europe and the rest of the world, which is already trading based on June contracts – was also weaker, down 8.9% at less than $26 a barrel.

Mr. Glickman said the historic reversal in pricing was a reminder of the strains facing the oil market and warned that June prices could also fall, if lockdowns remain in place. “I’m really not optimistic about the prospects for oil companies or oil prices,” he said.

OGUK, the business lobby for the UK’s offshore oil and gas sector, said the negative price of US oil would affect firms operating in the North Sea.

“The dynamics of this US market are different from those directly driving UK produced Brent but we will not escape the impact,” said OGUK boss Deirdre Michie.

“Ours is not just a trading market; every penny lost spells more uncertainty over jobs,” she said.

The oil industry has been struggling with both tumbling demand and in-fighting among producers about reducing output.

Earlier this month, Opec members and its allies finally agreed a record deal to slash global output by about 10%. The deal was the largest cut in oil production ever to have been agreed.

But many analysts say the cuts were not big enough to make a difference.

“It hasn’t taken long for the market to recognize that the Opec+ deal will not, in its present form, be enough to balance oil markets,” said Stephen Innes, chief global market strategist at Axicorp.

The leading exporters – Opec and allies such as Russia – have already agreed to cut production by a record amount.

In the United States and elsewhere, oil-producing businesses have made commercial decisions to cut output. But still the world has more crude oil than it can use.

And it’s not just about whether we can use it. It’s also about whether we can store it until the lockdowns are eased enough to generate some additional demand for oil products.

Capacity is filling fast on land and at sea. As that process continues it’s likely to bear down further on prices.

It will take a recovery in demand to really turn the market round and that will depend on how the health crisis unfolds.

There will be further supply cuts as private sector producers respond to the low prices, but it’s hard to see that being on a sufficient scale to have a fundamental impact on the market.

For US drivers, the decline in oil prices – which have fallen by about two-thirds since the start of the year – has had an impact at the pumps, albeit not as dramatic as Monday’s decline might suggest.

“The silver lining is, if you for various reasons actually need to be on the roads, you’re filling up for far less than you would have been even four months ago,” Mr. Glickman said. “The problem for most of us is even if you could fill up, where are you going to go?”

US President Donald Trump has said the government will buy oil for the country’s national reserve. But concern continues to mount that storage facilities in the US will run out of capacity, with stockpiles at Cushing, the main delivery point in the US for oil, rising almost 50% since the start of March, according to ANZ Bank.

Mr Innes said: “It’s a dump at all cost as no one, and I mean no one, wants delivery of oil with Cushing storage facilities filling by the minute.”